Skin in the game – education and workforce

Shifting the dial article

12 February 2018

Does our education system prepare us for the workforce?

The skills needed for well-paid jobs change just like everything else. More than a century ago, some common jobs included lamplighters, icemen and telegraph operators. Today you are unlikely to see anyone list their occupation as dunny man, milk deliverer or even TV repairer.

We largely rely on our education system to provide the skills and capabilities that new generations are going to need. So does Australia have the right system in place? One that will meet the needs of both employees and employers?

Probably not, according to the Productivity Commission in their recently released report Shifting the Dial: Five year Productivity Review.

Many of the recommendations put forward to improve our current education system are not new, but the Productivity Commission says that with economic shifts and little to no wage growth in recent years, now is the time we need to put these ideas into practice.

“Governments and commentators should be very wary of the seductive claim that something is well under way already in the areas to which we devote most attention. The Commission’s analysis is that the headline is often not supported by reality; or has not yet achieved the cooperation of all the necessary participants.”

Shifting the Dial: Five year Productivity Review, foreword, Productivity Commission, 2017

Student performance declining

It’s well known that our students’ performance in basic areas like English and maths have been on downward spiral compared with many of our international counterparts. This is despite education funding in real terms having significantly increased over the last ten years.

So should we be worried? After all, our students’ academic achievement is still above the OECD average. Well, how about these sobering figures. In mathematical literacy, an Australia 15 year old in 2015 had a mathematical aptitude equivalent to a 14 year old in 2000. We’ve lost a whole year’s worth of learning in 15 years. A whole year!

Our national participation rates in year 12 physics and advanced mathematics has fallen by more than 30 % from 1992 to 2012. That’s a huge number. We aren’t talking about slightly less people doing physics and advanced maths but almost a third less.

Some problems we should fix

The report says that some of the problems Australia faces that will affect our ability to produce an appropriately skilled workforce are: low teacher effectiveness; too much teaching ‘out of field’; a Vocational and Education Training (VET) system that is in disarray and a university system that places too much emphasis on making money out of students to fund research and publishing, and too little on teaching skills and student outcomes.

In seeking change, we need to acknowledge that for many of us jobs are more than just a source of income. They provide opportunities for social interaction, a source of self-esteem and often a feeling of purpose. If we want people to be able to get the types of jobs that provide all this then we need some things to change.

As the system designer, primary funder and supplier of formal education, this change needs to come from both State and Federal governments.

Strong foundations – early school

We need to stop the steady decline of student performance. Strong foundational skills have immediate value, but they also give people a greater capacity to learn to learn. This provides insurance against the inevitable dating of past knowledge and established occupational tasks.

We know that the tasks people are required to undertake in many occupations will change and indeed are changing. Skills such as problem solving, communicating effectively and working in a team are foundational skills that people can use in just about any career. These are skills that can be taught from a young age.

Once more with feeling – good teachers are key

The report says governments need to ‘improve the education outcomes of school students’ by ensuring that the best possible teaching methods are being used in the school system, supported by an educational evidence base and the employment of high-quality, well-trained teachers in the fields where they are needed.

The report mentions teaching out of field and gives an example that in information technology (IT) about 30% of year 7 to 10 teachers haven’t studied the subject at second year territory level or above or been trained in teach methodology for that subject. Given that IT skills seem like a necessity for future jobs, we must have qualified people teach in schools.

Some of the solutions recommended in the report for declining student performance concentrate on teacher quality. It suggests a better approach to the workforce development of teachers including use of salary differentials, so teachers who teach well are rewarded.

“Countries with high academic outcomes have tended to pursue deliberate policies to attract the most able people into teaching, including offering salaries and working conditions that enable teaching to compete with other professions.”

Shifting the Dial: Five year Productivity Review, pg 90, Productivity Commission, 2017

The idea of improving the standard of teachers is not novel and nor is it easy to implement rapidly by recruiting new teachers. The fact that the stock of existing teachers is much larger than the inflow of new ones means that there is a strong and immediate need for high quality professional development of existing teachers.

Putting Australia’s VET system together again

At the heart of Australia’s VET system is the objective of ensuring that employers can hire employees who are work-ready. Yet employers complain of qualifications that do not meet their needs and individuals find it hard to know where to obtain a quality training program. The large number of employers who don’t participate in accredited training and find other ways to skill their workers is symptomatic of lack of employer confidence in the VET system.

About half of all employers use unaccredited training, with close to 90 % of those employers being satisfied with the training. In contrast, only 76 % of employers using the VET system to train workers in vocational qualifications were satisfied.

Australia’s VET system is fortunately not like Humpty Dumpty. Yes, it is currently a mess and many have lost confidence in it, but repair is possible. Although policy renovation is underway, it will take some time before confidence and stability returns to the sector. Now is a good time to take further measures to ensure VET turn out people with work-ready skills that employers want and value.

One future‑oriented change is a move to rate students on not just whether they can perform a given task but how well they can perform that task. In many occupations, there can be a big difference between a capacity to do a task and being good at it. A new rating system would start with a few skills where proficiency is central to employers, and then expand Such a move would create incentives for students to perform well and to make it easier for employers to recruit and job match.

Full time employment rates for university graduates are declining

The number of young Australians attending University has never been higher — growth that might partly reflect the recent years of chaos in the VET sector. Nearly 40 % of 30-39 year olds held a bachelor degree or higher in 2016. Yet university students are increasingly not getting good outcomes from their education.

Full-time employment rates for recent graduates have been declining, even as the Australian economy has continued to grow.

Over a quarter of recent graduates believe they are employed in full-time in roles unrelated to their studies and believe their degree added no value.

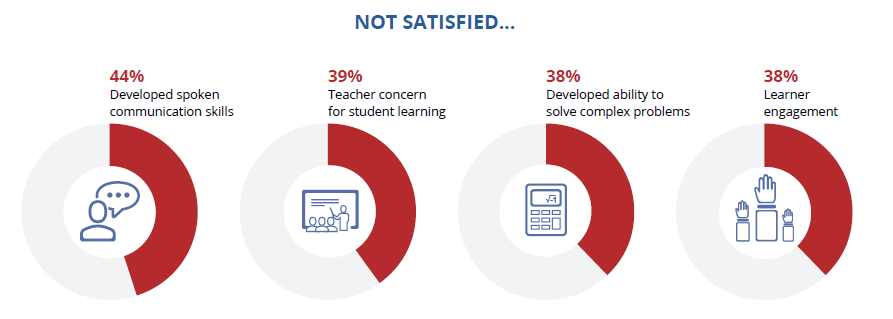

However, the report shows though that there is strong scope to improve outcomes from universities. It backs up this point with data that shows that many students aren’t satisfied with their courses and this is reinforced by the high number of students that don’t complete their courses.

In 2014, more than 26% of students had not completed their degree program within nine years of commencing. Having over a quarter of students not complete their qualifications represents a significant loss of resources for those students (in time, effort and money), as well as for taxpayers.

“It’s not just students that are dissatisfied. Many employers are also not satisfied with the quality of recent graduates, with about one in six supervisors saying that they were unlikely to consider or would be indifferent to graduates from the same university.”

Shifting the Dial: Five year Productivity Review, pg 103, Productivity Commission, 2017

Focus less on research prestige and more on student outcomes

The report says universities are focused more on research prestige and less on teaching outcomes. Academics are rewarded for excellent research (a good outcome), but not for excellent teaching (a bad outcome). Students can be loaded with HELP debt, which the Australian Government may ultimately have to pay even if the course quality and educational outcomes are poor.

Universities have no financial ‘skin in the game’. Accountability for better outcomes should go deeper than just providing would-be students with information about universities’ teaching performance.

Though few actions have been undertaken, the Australian Consumer Law now applies to the services of universities. In principle, this means that a person receiving a shoddy education has a right to redress. If exercising this right under the existing law proves too cumbersome or difficult, Australia might well consider emulating the United Kingdom where the right for redress is expressly included in the law, including a potential right to repeat the course at no cost.

Direct financial incentives may also play a role in reform. One possibility is that universities bear a moderate share of Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) for students who don’t complete their qualifications.

This would provide incentives to universities to match students to suitable courses and ensure those courses are useful to students and employers. But as in the famous anatomical ditty that the “shin bone is connected to the knee bone, the knee bone is connected to the thigh bone...”, the Commission argues that the many parts of the university system are intertwined. So broader reforms are probably needed too.

Other things

The Productivity Commission’s report also covers areas like trialling more innovative ways of learning, better focusing on re-training people with generic skills like communication, team work and computer skills.

If you’re interested in education and skills it’s a must read and you can find the report online. Chapter 3, titled future skills and work, is where you will find the information and recommendations on Australia’s education and training systems.