Report on Government Services 2022

PART B: RELEASED ON 3 FEBRUARY 2022

B Child care, education and training

Impact of COVID-19 on data for the Child care, education and training sector overview

COVID-19 may affect data in this report in a number of ways. This includes in respect of actual performance (that is, the impact of COVID-19 on service delivery during 2020 and 2021 which is reflected in the data results), and the collection and processing of data (that is, the ability of data providers to undertake data collection and process results for inclusion in the report).

Various restrictions introduced from March 2020 including travel restrictions, shutting down of non-essential services, stimulus packages, free child care for working parents and social distancing rules are likely to have had an impact on the child care, education and training sector. Any impacts which are specific to the service areas covered in this Report are noted in sections 3, 4, and 5.

Main aims of services within the sector

The child care, education and training (CCET) sector services aim to care for and develop the capacities and talents of children and students, to ensure that they have the necessary knowledge, understanding, skills and values for a productive and rewarding life.

Services included in the sector

- Early childhood education and care (ECEC)

Services related to early childhood and out-of-school care, comprising child care and preschool services. - School education

Formal schooling, consisting of six to eight years of primary school education followed by five to six years of secondary schooling. - Vocational education and training (VET)

Tertiary education delivered by technical and further education (TAFE) institutes and other VET providers. - Higher education — education delivered by universities (not included as a service specific-chapter in this Report).

Detailed information on the equity, effectiveness and efficiency of service provision and the achievement of outcomes for the ECEC, Schools and VET service areas is contained in the service-specific chapters.

Note: Data tables are referenced by table xA.1, xA.2, etc, with x referring to the section or overview. For example, table BA.1 refers to data table 1 for this sector overview.

Government expenditure in the sector

Expenditure on CCET services is significant. Total Australian, State and Territory government recurrent expenditure on CCET services was $89.7 billion, around 29.8 per cent of total government expenditure on services covered in this Report. School education was the largest contributor ($70.6 billion, table 4A.10), followed by ECEC ($12.4 billion, table 3A.4) and VET ($6.6 billion, table 5A.1).

For higher education, expenditure data are not collected for this Report, but in the ABS’s Government Finance Statistics (GFS) report1 it was around $32.0 billion in 2019‑20.

Flows in the sector

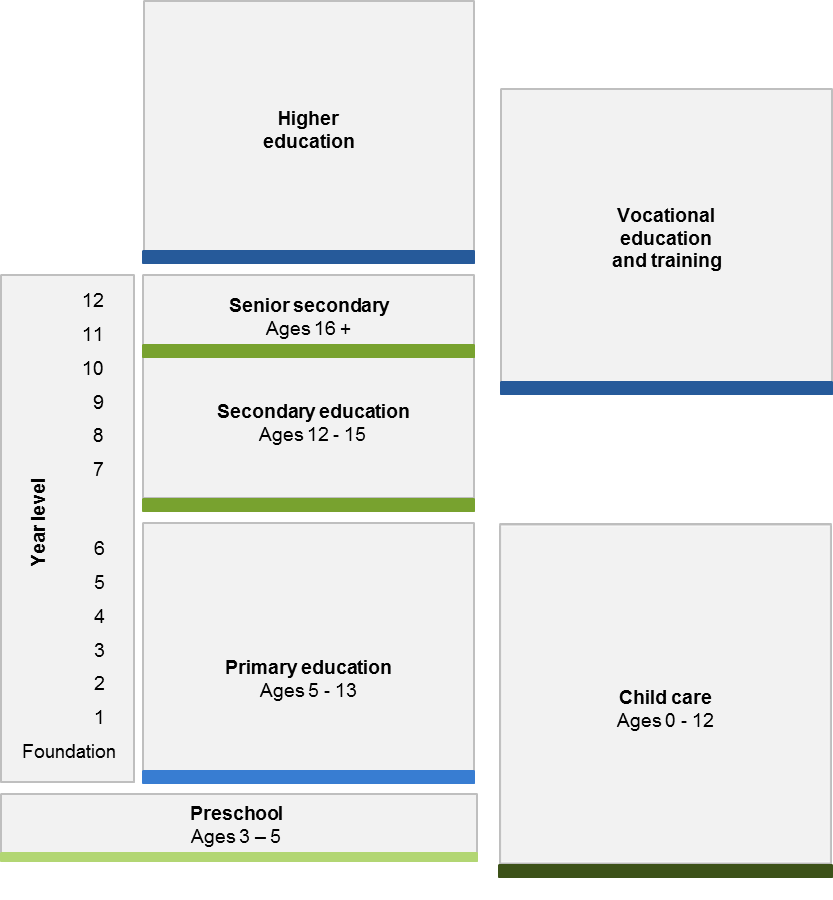

The formal education and training system starts at preschool and continues through the years of compulsory schooling (generally year 10 — see sub-section 4.1, section 4) and post school education. Child care provides services to children aged 0–12 years, in the years before preschool begins and in out-of-school care during the primary school years (figure B.1). Formal learning does not always progress in a linear fashion from preschool to school (primary and secondary) to VET or university, as there are many learning pathways an individual might take over their lifetime.

Figure B.1 Outline of the Australian childcare, education and training systema, b, c

a There are different starting ages and names for preschool (see section 3, table 3.1) and school education (see section 4, context) across jurisdictions. b In SA primary school spans pre‑year 1 to year 7 and secondary school spans years 8 to 12. Year 7 Government school students will be taught in high school from term 1 2022. c Providers can deliver qualifications in more than one sector, all subject to meeting the relevant quality assurance requirements.

Source: Australian, State and Territory governments (unpublished).

Participation in education and training is particularly important for younger people. Nationally in 2021, 64.5 per cent of 15–24 year olds were enrolled in education and training (85.7 per cent of 15–19 year olds and 45.0 per cent of 20–24 year olds), compared to 8.3 per cent of 25–64 year olds (figure B.2).

Young people’s successful transition from compulsory schooling to education, training and employment is particularly important, with a positive relationship between completion of year 12 and subsequent engagement (figure B.3). Nationally in 2021, 73.9 per cent of 17–24 year old school leavers were fully participating in education, training and/or employment, an increase from 2020 (69.3 per cent) following a decrease from 2019 (74.0 per cent).

Sector-wide indicators

Two sector-wide indicators of governments’ aim to develop the capacities and talents of children and students to ensure necessary knowledge, understanding, skills and values for a productive and rewarding life are reported.

- Achievement of foundation skills — proportion of 20–64 year olds who have achieved literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology rich environments (PSTRE) competencies.

- Attainment of qualifications — proportion of 20–64 year olds with qualifications at Certificate III level or above.

High or increasing levels of the achievement of foundation skills or attainment of qualifications indicates an improvement in education and training outcomes.

Achievement of foundation skills

Achievement of foundation skills is a proxy indicator as it measures only a subset of the skills and values needed for a productive and rewarding life. Data are sourced from the OECD survey Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)2 that measures adult skills and competencies for literacy, numeracy and PSTRE. Below level 1 represents the poorest level of skill attainment and level 5 the highest level of skill attainment for literacy and numeracy; level 3 represents the highest level of PSTRE skill attainment.

- In 2011-12, the proportion of the population aged 20–64 years who achieved at level 3 or above was 56.7 per cent for literacy and 46.3 per cent for numeracy (tables BA.16–17).

- Additional data on the proportions of the population aged 15–74 years across all PIAAC literacy, numeracy and PSTRE skill levels in 2011‑12 are in tables BA.16–18.

Attainment of qualifications

Attainment of qualifications is a proxy indicator for skills as it understates the skill base because it does not capture skills acquired through partially completed courses, courses not leading to a formal qualification, and informal learning.

Nationally in 2021, 65.4 per cent of 20–64 year olds had a qualification at Certificate III level or above (figure B.4). Qualification rates at Certificate level III or above are highest for 35–39 year olds and have been increasing over time. The proportion is lower across the remaining working age population age groups. Data by Indigenous status are in table BA.15. Data for 20-24 year olds who have completed year 12 (or equivalent) or Certificate III level or above by remoteness are in table BA.11.

Download data tables

These data tables relate to the sector as a whole. Data specific to individual service areas are in the data tables under the relevant service area.

- Child care, education and training data tables (XLSX - 139 Kb)

- Child care, education and training dataset (CSV - 246 Kb)

See the Sector overview text and corresponding table number in the data tables above for detailed definitions, caveats, footnotes and data source(s).

Footnotes

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (unpublished), Government Finance Statistics, Education, Australia, 2019-20, Canberra. Expenditure data from the GFS are not comparable to expenditure data collected for this Report. Locate Footnote 1 above

- The most recent available data are from the first cycle of the PIAAC and are in respect of 2011-12. The second cycle of the PIAAC is due to be conducted in 2022-23 with data anticipated to be available in 2023-24. Locate Footnote 2 above