Report on Government Services 2022

Part B, section 4: LATEST UPDATE: 7 JUNE 2022

4 School education

LATEST UPDATE 7 JUNE 2022:

Indicator results for:

- Attendance and participation by selected equity group, 2021 data

- Attendance, 2021 data

- Retention, 2021 data

Context on:

Impact of COVID-19 on data for the School education section

COVID-19 may affect data in this Report in a number of ways. This includes in respect of actual performance (that is, the impact of COVID-19 on service delivery during 2020 and 2021 which is reflected in the data results), and the collection and processing of data (that is, the ability of data providers to undertake data collection and process results for inclusion in the Report).

For the School education section, there has been some impact on the data that is attributable to COVID-19 but this has not affected the comparability of any indicators. These impacts are primarily due to the social distancing restrictions implemented from March 2020 and associated economic downturn, which may have affected 2020 data for the post school destination indicator.

This section focuses on performance information for government-funded school education in Australia.

The Indicator Results tab uses data from the data tables to provide information on the performance for each indicator in the Indicator Framework. The same data are also available in CSV format.

- Context

- Indicator framework

- Indicator results

- Indigenous data

- Key terms and references

Objectives for school education

Australian schooling aims for all young Australians to become successful lifelong learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed members of the community positioning them to transition to further study and/or work and successful lives. It aims for students to improve academic achievement and excel by international standards.

To meet this vision, the school education system aims to:

- engage all students and promote student participation

- deliver high quality teaching of a world-class curriculum.

Governments aim for school education services to meet these objectives in an equitable and efficient manner.

The vision and objectives align with the educational goals in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration (EC 2019) and the National School Reform Agreement (NSRA) (COAG 2018).

Service overview

Schooling aims to provide education for all young people. The structure of school education varies across states and territories.

Compulsory school education

Entry to school education is compulsory for all children in all states and territories, although the child age entry requirements vary by jurisdiction (ABS 2021). In 2020, minimum starting ages generally restrict enrolment to children aged between four-and-a-half and five years at the beginning of the year (ABS 2021). (See section 3, for more details.)

National mandatory requirements for schooling — as agreed in the National Youth Participation Requirement (NYPR) — came into effect through relevant State and Territory government legislation in 2010. Under the NYPR, all young people must participate in schooling until they complete year 10; and if they have completed year 10, in full time education, training or employment (or combination of these) until 17 years of age (COAG 2009). Some State and Territory governments have extended these requirements for their jurisdiction.

Type and level of school education

Schools are the institutions within which organised school education takes place (see the 'Key terms and references' tab for a definition of ‘school’) and are differentiated by the type and level of education they provide:

- Primary schools provide education from the first year of primary school — known as the ‘foundation year’ in the Australian Curriculum (see the 'Key terms and references' tab for the naming conventions used in each state and territory). Primary school education extends to year 6 (year 7 in SA until 2022 when it will be high school). (Prior to 2015, primary school education also extended to year 7 in Queensland and WA.)

- Secondary schools provide education from the end of primary school to year 12

- Special schools provide education for students that exhibit one or more of the following characteristics before enrolment: mental or physical disability or impairment; slow learning ability; social or emotional problems; or in custody, on remand or in hospital (ABS 2021).

Affiliation, ownership and management

Schools can also be differentiated by their affiliation, ownership and management, which are presented for two broad categories:

- Government schools are owned and managed by State and Territory governments

- Non-government schools, including Catholic and Independent schools, are owned and managed by non-government establishments.

Roles and responsibilities

State and Territory governments are responsible for ensuring the delivery and regulation of schooling to all children of school age in their jurisdiction. State and Territory governments provide most of the school education funding in Australia, which is administered under their own legislation. They determine curricula, register schools, regulate school activities and are directly responsible for the administration of government schools. They also provide support services used by both government and non-government schools. Non-government schools operate under conditions determined by State and Territory government registration authorities.

From 1 January 2018 the Australian Government introduced the Quality Schools Package replacing the Students First funding model which had been in effect since 1 January 2014. States and territories will also contribute funding under the Quality schools Package. More information on these funding arrangements can be found under '6a. Efficiency' on the 'Indicator results' tab.

The Australian Government and State and Territory governments work together to progress and implement national policy priorities, such as: a national curriculum; national statistics and reporting; national testing; and, teaching standards (PM&C 2014).

Funding

Nationally in 2019-20, government recurrent expenditure on school education was $70.6 billion, a 5.9 per cent real increase from 2018-19 (table 4A.10). State and Territory governments provided the majority of funding (68.3 per cent) (figure 4.1).

Government schools accounted for $52.6 billion (74.5 per cent), with State and Territory governments the major funding source ($44.2 billion, or 83.9 per cent of government schools’ funding). Non-government schools accounted for $18.0 billion (25.5 per cent), with the Australian Government the major funding source ($13.9 billion, or 77.4 per cent of non-government schools funding) (table 4A.10).

The share of government funding to government and non-government schools varies across jurisdictions and over time according to jurisdictional approaches to funding schools (see '6a. Efficiency' on the 'Indicator results' tab) and is affected by the characteristics of school structures and the student body in each state and territory.

This Report presents expenditure related to government funding only, not to the full cost to the community of providing school education. Caution should be taken when comparing expenditure data for government and non-government schools, because governments provide only part of school funding. Governments provided 62.2 per cent of non-government school funding in 2020, with the remaining 37.8 per cent sourced from private fees and fund raising (Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment unpublished).

Size and scope

Schools

In 2021, there were 9581 schools in Australia (6256 primary schools, 1442 secondary schools, 1374 combined schools, and 509 special schools) (table 4A.1). The majority of schools were government owned and managed (69.8 per cent) (table 4A.1).

Settlement patterns (population dispersion), the age distribution of the population and educational policy influence the distribution of schools by size and level in different jurisdictions. Data on school size and level are available from Schools Australia, 2021 (ABS 2022).

Student body

There were 4.0 million full time equivalent (FTE) students enrolled in school nationally in 2021 (table 4A.3). Whilst the majority of students are full time, there were 10 978 part time students in 2021 (predominantly in secondary schools) (ABS 2022).

- Government schools had 2.6 million FTE students enrolled (65.0 per cent of all FTE students). This proportion has decreased from 65.6 per cent in 2020 and is the lowest in the last 10 years of data reported (table 4A.3).

- Non-government schools had 1.4 million FTE students enrolled (35.0 per cent of all FTE students).

- The proportion of students enrolled in government schools is higher for primary schools than secondary schools (table 4A.3).

A higher proportion of FTE students were enrolled in primary schools (56.3 per cent) than in secondary schools (43.7 per cent) (table 4A.3). NT and SA have the highest proportions of FTE students enrolled in primary school education (59.9 per cent and 59.6 per cent respectively). SA is the only jurisdiction that still includes year 7 in primary school.

The enrolment rate is close to 100 per cent for Australian children aged 15 years (consistent with requirements under the NYPR), but decreases as ages increase. Nationally in 2021, 98.1 per cent of Australian children aged 15 years were enrolled at school, declining to 92.8 per cent of 16 year olds and 82.6 per cent of 17 year olds. Data are available for 15–19 year olds by single year of age and totals in table 4A.4.

Nationally, government schools had a higher proportion of students from selected equity groups than non-government schools, including for:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students — 7.9 per cent of government school students and 3.0 per cent of non-government school students in 2021 (table 4A.5)

- students from a low socio-educational background — 30.8 per cent of government school students and 12.6 per cent of non-government school students in 2020 (table 4A.6)

- geographically remote and very remote students — 2.3 per cent of government school students and 1.0 per cent of non-government school students in 2020 (table 4A.8).

For students with disability, 20.8 per cent, 19.1 per cent, and 19.6 per cent of students at government, Catholic, and independent schools, respectively, required an education adjustment due to disability (table 4A.7). Data by level of adjustment are in table 4A.7.

School and Vocational Education and Training (VET)

School-aged people may participate in VET by either participating in ‘VET in Schools’, or (see section 5) remain engaged in education through a Registered Training Organisation. Nationally in 2020, there were 241 200 VET in Schools students (NCVER 2020). Overall, 392 100 people aged 15–19 years successfully completed at least one unit of competency as part of a VET qualification at the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) Certificate II level or above (at a school or Registered Training Organisation) (table 4A.9).

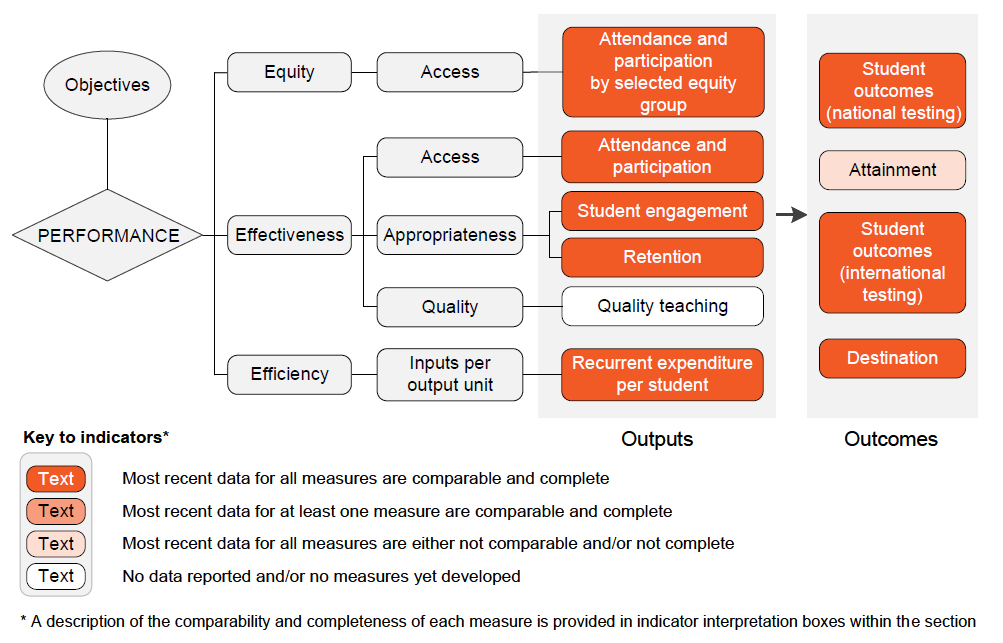

The performance indicator framework provides information on equity, efficiency and effectiveness, and distinguishes the outputs and outcomes of School education.

The performance indicator framework shows which data are complete and comparable in this Report. For data that are not considered directly comparable, text includes relevant caveats and supporting commentary. Section 1 discusses data comparability and completeness from a Report-wide perspective. In addition to the contextual information for this service area (see Context tab), the Report’s statistical context (Section 2) contains data that may assist in interpreting the performance indicators presented in this section.

Improvements to performance reporting for School education are ongoing and include identifying data sources to fill gaps in reporting for performance indicators and measures, and improving the comparability and completeness of data.

Outputs

Outputs are the services delivered (while outcomes are the impact of these services on the status of an individual or group) (see section 1). Output information is also critical for equitable, efficient and effective management of government services.

Outcomes

Outcomes are the impact of services on the status of an individual or group (see section 1).

An overview of the School education services performance indicator results are presented. Different delivery contexts, locations and types of clients can affect the equity, effectiveness and efficiency of school education services.

Information to assist the interpretation of these data can be found with the indicators below and all data (footnotes and data sources) are available for download from Download supporting material. Data tables are identified by a ‘4A’ prefix (for example, table 4A.1).

All data are available for download as an excel spreadsheet and as a CSV dataset — refer to Download supporting material. Specific data used in figures can be downloaded by clicking in the figure area, navigating to the bottom of the visualisation to the grey toolbar, clicking on the 'Download' icon and selecting 'Data' from the menu. Selecting 'PDF' or 'Powerpoint' from the 'Download' menu will download a static view of the performance indicator results.

1. Attendance by selected equity group

‘Attendance by selected equity group’ is an indicator of governments’ objective for school education services to be provided in an equitable manner.

‘Attendance by selected equity group’ compares the attendance rate of those in the selected equity group (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, students in remote/very remote areas) with the attendance rate of those outside the selected equity group (non‑Indigenous students, students in major cities and regional areas).

Similar rates of attendance for those within and outside the selected equity groups indicates equity of access.

The student attendance rate is the number of actual full time equivalent student days attended by full time students as a percentage of the total number of possible student attendance days attended over the period.

Nationally in 2021, attendance rates across years 1–10 decreased as remoteness increased, except for NSW and Tasmania where there were higher rates for very remote students than remote students, with the decrease greater for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students than for non-Indigenous students (figure 4.2a). This pattern was similar for government and non-government schools (table 4A.21).

Nationally in 2021, non‑Indigenous students in all schools had higher attendance rates than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students across all year levels in all jurisdictions. This pattern was similar for government and non‑government schools (figure 4.2b and tables 4A.18-21).

The student attendance level is the proportion of full time students whose attendance rate is greater than or equal to 90 per cent over the period. Analysis of the attendance level can highlight ‘at risk’ populations (where a large proportion of individuals have had low attendance over the school year). Data on the student attendance level by Indigenous status and remoteness are in tables 4A.22–24.

2. Attendance

‘Attendance’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that school education services promotes student participation.

‘Attendance’ is defined by the student attendance rate — the number of actual full time equivalent student days attended by full time students as a percentage of the total number of possible student attendance days attended over the period.

Higher or increasing rates of attendance are desirable. Poor attendance has been related to poor student outcomes, particularly once patterns of non‑attendance are established (Hancock et al. 2013).

Nationally in 2021, across all schools attendance rates decreased from year 7 to year 10 — from 91.2 per cent to 87.0 per cent (table 4A.20). For years 7–10 combined, attendance rates are higher at non‑government schools (91.7 per cent) than government schools (86.8 per cent).

Nationally in 2021, the attendance rate for all school students across year levels 1–6 was 92.3 per cent (figure 4.3). The year 1–6 attendance rates have decreased slightly since 2015 (slightly over 1 percentage point) with similar decreases across most jurisdictions (table 4A.20).

3. Student engagement

‘Student engagement’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that school education services engage all students.

‘Student engagement’ is defined as encompassing the following three dimensions:

- behavioural engagement — which may be measured by identifiable behaviours of engagement, such as school attendance, attainment and retention

- emotional engagement — which may be measured by students’ attitudes to learning and school

- cognitive engagement — which may be measured by students’ perception of intellectual challenge, effort or interest and motivation (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris 2004).

It is measured using data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) — a triennial assessment of 15 year‑old students conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that also collects student and school background contextual data. PISA collects information on one aspect of emotional engagement — students’ sense of belonging at school. Students’ level of agreement to six statements are combined to construct a Sense of Belonging as School Index (table 4A.25).

Higher or increasing scores on the Index illustrate a greater sense of belonging at school, which is desirable. The index is standardised to have a mean of 0 across OECD countries. Higher values of the index indicate a greater sense of belonging at school than the OECD average and lower values indicate a lesser sense of belonging at school than the OECD average.

These data should be interpreted with caution, as they are limited to one aspect of emotional engagement and captured for students at a single age (students aged 15 years).

National data are not currently agreed to report against behavioural or cognitive engagement. However contextual information is provided on State and Territory government student engagement surveys, where they have been conducted (table 4.1). These surveys collect information from students across the behavioural, emotional, and cognitive domains of engagement. In addition, some aspects of behavioural engagement are captured via the attendance, retention and attainment indicators.

Nationally in 2018, the proportion of 15 year old students that agreed/disagreed with the following statements was:

- I make friends easily at school (agree) — 75.6 (± 1.0) per cent

- I feel like I belong at school (agree) — 68.2 (± 1.0) per cent

- Other students seem to like me (agree) — 85.3 (± 0.9) per cent

- I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school (disagree) — 72.9 (± 1.0) per cent

- I feel awkward and out of place at my school (disagree) — 75.2 (± 0.9) per cent

- I feel lonely at school (disagree) — 80.7 (± 0.9) per cent (figure 4.4).

From these responses, the Sense of Belonging at School Index for Australian students aged 15 years was ‑0.19 (± 0.02) (figure 4.4). The score, which is below the 2018 OECD average, varied across jurisdictions. National data on the Sense of Belonging at School Index, by special needs group (sex, Indigenous status, geolocation, and socioeconomic background) are included in table 4A.26.

Sense of belonging at school has been measured in four cycles of PISA: in 2003, 2012 2015 and 2018. Nationally, over this 12 year period, students’ agreement/disagreement with the Sense of Belonging Index statements have declined (ACER 2018, table 4A.25).

Table 4.1 School student engagement survey results

Key Features: | Student engagement data are collected from NSW government schools twice a year, in Term 1 and Term 3, for students in Years 4 to 6 (primary schools) and Years 7 to 12 (high schools). The surveys are available to all department schools, and all students within scope in participating schools. |

|---|---|

Domain: | Data are collected on the key domains of student engagement: behavioural, emotional and cognitive. |

Statistics: | Student engagement is multi-dimensional and differs across school years. As such, there is no single indicator of engagement. Longitudinal modelling conducted by the NSW Department of Education shows that various drivers of student engagement can impact student outcomes. Students who demonstrate positive attitudes towards attendance and behaviour, and are academically motivated can be several months ahead in their learning compared with students who do not demonstrate these traits. Similarly, students who experience high academic expectations and who have a positive sense of belonging and high levels of advocacy at school experience a range of positive schooling outcomes. |

Link: | More information, including results from longitudinal modelling, is available from the NSW Department of Education website: https://education.nsw.gov.au/student-wellbeing/tell-them-from-me.html |

Key Features: | The annual Attitudes to School Survey gathers data to support: (1) student wellbeing; (2) engagement; (3) school improvement; and (4) planning in Victorian government schools. The online survey captures the attitudes and experiences of students in Years 4 to 12 and is designed principally to inform improvement opportunities within government schools. |

|---|---|

Domain: | The Attitudes to School Survey measures aspects of student’s emotional and cognitive engagement. |

Statistics: | Results for 2020 indicate that majority of Victorian government school students feel connected to their schooling. On a five point Likert scale, students in Year 5 to 6 record a mean score of 4.1 and students in Year 7 to 9 record a mean score of 3.6. |

Link: | https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/data-collection-surveys/policy |

Key Features: | The Queensland Engagement and Wellbeing Survey was piloted in 2020, and offered to all Queensland state schools on a voluntary basis in mid-2021. |

|---|---|

Domain: | The Survey measures wellbeing and engagement across 12 different domains, including resilience, school climate, sense of belonging, motivation and perseverance, academic self-concept, personal social capabilities, general life satisfaction, future outlook and aspirations, relationships with peers, with teachers and at home, and general health. |

Statistics: | As the Survey was offered state-wide for the first time in mid-2021, statistics are not yet available. |

Link: |

| .. |

Key Features: | Data sourced from the Wellbeing and Engagement Collection. The window for completion was 15 March to 2 April, 2021. Data are collected annually. The purpose of the survey is to seek students’ views about their wellbeing and engagement with school. Students in Years 4 to 12 participated in the collection. The survey is voluntary at a school, student and question level – 93 per cent of all public schools participated. The survey asks students about their social and emotional wellbeing; school relationships and engagement and learning in school; and physical health and wellbeing and after school activities. Students’ answers are kept confidential. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Domain: |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statistics: |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Link: |

Key features: | The Tasmanian Department of Education conducts an annual Student Wellbeing and Engagement Survey for students in Years 4 to 12 in Tasmanian Government schools. This survey was first run in 2019 and with most recent results from 2020. The Student Wellbeing survey supports the 2018-2021 Department of Education Child and Student Wellbeing Strategy: Safe, Well and Positive Learners which was published on 28 June 2018 and was developed to support the Department’s Wellbeing Goal under the 2018-2021 Department of Education Strategic Plan, Learners First: Every Learner Every Day . The Wellbeing Strategy supports the Tasmanian Child and Youth Wellbeing Framework and adopts the six Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth wellbeing domains: Loved and Safe, Material Basics, Healthy, Learning, Participating and Positive sense of culture and identity. |

|---|---|

Domain: | The domain of Learning within the Student Wellbeing and Engagement Survey measures the following subdomains of engagement:

|

Statistics: | The levels of engagement are determined based on respondents who indicated medium or high wellbeing, as a proportion of all responses across the questions associated with the three Learning subdomains associated with engagement in the Student Wellbeing and Engagement Survey. In 2020 these are:

|

Link: | Information on the Student Wellbeing and Engagement Survey may be found at: https://www.education.tas.gov.au/about-us/projects/child-student-wellbeing/student-wellbeing-survey-3/ Additional information on the Department’s Student and Child Wellbeing Strategy may be found at: https://www.education.tas.gov.au/about-us/projects/child-student-wellbeing/ |

Key Features: | The ACT conducts the Australian School Climate and School Identification Measurement Tool (ASCSIMT) survey in all public schools. All students in Years 4 to 12, school staff and parents of all students from preschool to Year 12 are invited to complete the survey. The ASCSIMT was developed in partnership with the Australian National University. The survey explores the relationships between school climate and the sense of belonging of students and how these relate to student behavioural and emotional engagement and to a number of domains of student wellbeing and behaviour. The survey is conducted every August in conjunction with the School Satisfaction Survey. The survey allows for longitudinal research into student engagement. |

|---|---|

Domain: | The domains addressed by the survey include:

|

Statistics: | Collection of the survey was postponed in 2021 because of COVID-19. |

Key features: | The NT Department of Education annual School Survey collects the opinions of staff, students and their families about school performance, culture and services. The NT School Survey is conducted in all Northern Territory Government schools across Weeks 4 – 6 of Term 3. There are three different versions of the survey designed to specifically target: students in Years 5 to 12, parents and carers of students at all year levels and school-based staff including teaching and administration staff. |

|---|---|

Domain: | The NT School Survey contains questions that aim to provide schools with key insights into student wellbeing, engagement, and learning experiences from the perspective of students, parents and school staff. |

Link: | https://education.nt.gov.au/statistics-research-and-strategies/school-survey |

Source: State and Territory governments (unpublished).

4. Retention

‘Retention’ to the final years of schooling is an indicator of governments’ objective that the school education system aims to engage all students and promote student participation.

‘Retention’ (apparent retention rate) is defined as the number of full time school students in year 10 that continue to year 12.

The term ‘apparent’ is used because the measures are derived from total numbers of students in each of year 10 and year 12, not by tracking the retention of individual students. Uncapped rates (rates that can be greater than 100 per cent) are reported for time series analysis. Care needs to be taken in interpreting the measures as they do not take account of factors such as:

- students repeating a year of education or returning to education after a period of absence

- movement or migration of students between school sectors, between states/territories and between countries

- the impact of full fee paying overseas students.

These factors may lead to uncapped apparent retention rates that exceed 100 per cent.

This indicator does not include part time or ungraded students (which has implications for the interpretation of results for all jurisdictions) or provide information on students who pursue year 12 (or equivalent qualifications) through non‑school pathways.

Apparent retention rates are affected by factors that vary across jurisdictions. For this reason, variations in apparent retention rates over time within jurisdictions may be more useful than comparisons across jurisdictions.

A higher or increasing rate is desirable as it suggests that a larger proportion of students are continuing in school, which may result in improved educational outcomes.

Nationally in 2021, the apparent retention rate from year 10 to year 12 was 81.6 per cent, an increase from 79.3 per cent in 2012 but below the peak of 83.3 per cent in 2017. The rate was 77.2 per cent for government schools and 87.9 per cent for non-government schools. This pattern was similar for both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and non-Indigenous students (figure 4.5).

Consistent with the NYPR mandatory requirement that all young people participate in schooling until they complete year 10, the apparent retention rate for all schools from the commencement of secondary school (at year 7 or 8) to year 10 has remained above 97 per cent in all jurisdictions (other than the NT) since 2011. Nationally, the retention rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students was over 97 per cent in 2021, but lower than that of non‑Indigenous students (table 4A.27).

5. Quality teaching

‘Quality teaching’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that school education delivers high quality teaching of a world‑class curriculum. A good quality curriculum provides the structure for the provision of quality learning (UNESCO‑IBE 2016), while teachers are the single most important ‘in‑school’ influence on student achievement (Hattie 2009). Teacher quality can influence student educational outcomes both directly and indirectly, by fostering a positive, inclusive and safe learning environment (Boon 2011).

‘Quality teaching’ is defined in relation to the teaching environment, including the quality of the curriculum and the effectiveness of the teachers. Teachers are considered effective where they:

- create an environment where all students are expected to learn successfully

- have a deep understanding of the curriculum and subjects they teach

- have a repertoire of effective teaching strategies to meet student needs

- direct their teaching to student needs and readiness

- provide continuous feedback to students about their learning

- reflect on their own practice and strive for continuous improvement (PC 2012).

This indicator may be measured in future by student responses to survey questions on their perceptions of the teaching environment including the curriculum. High or increasing proportions of students indicating positive responses to the teaching environment are desirable.

Data are not yet available for reporting against this indicator.

6. Recurrent expenditure per student

‘Recurrent expenditure per student’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide school education services in an efficient manner.

‘Recurrent expenditure per student’ is defined as total government recurrent expenditure per FTE student, reported for government schools and for non‑government schools. Government recurrent expenditure per FTE student includes estimates for UCC for government schools (see '6a. Efficiency' on the Indicator results tab). UCC is not included for non‑government schools.

FTE student numbers (table 4A.3) are drawn from the ABS publication Schools Australia 2020 (ABS 2021) and averaged over two calendar years to match the financial year expenditure data. From 2018-19, FTE enrolled students used to derive NSW and total Australian recurrent expenditure per student for government and all schools excludes Norfolk Island Central School FTE enrolments.

Holding other factors constant, a low or decreasing government recurrent expenditure or staff expenditure per FTE student may represent better or improved efficiency.

Care should be taken in interpretation of efficiency data as:

- a number of factors beyond the control of governments, such as economies of scale, a high proportion of geographically remote students and/or a dispersed population, and migration across states and territories, may influence expenditure

- while high or increasing expenditure per student may reflect deteriorating efficiency, it may also reflect changes in aspects of schooling (increasing school leaving age, improving outcomes for students with special needs, broader curricula or enhancing teacher quality), or the characteristics of the education environment (such as population dispersion).

- Reporting requirements and methodologies may vary between years. Refer to footnotes in the data tables.

Nationally in 2019-20, government recurrent expenditure per FTE student in all schools was $17 779 (figure 4.6). Between 2010‑11 and 2019-20, real government expenditure per FTE student increased at an average rate of 2.2 per cent per year (table 4A.14).

Nationally in 2019‑20, government recurrent expenditure per FTE student in non‑government schools was $13 189 (does not include UCC). Between 2010‑11 and 2019‑20 real government expenditure per FTE student increased at an average rate of 3.9 per cent per year.

Nationally in 2019‑20, government recurrent expenditure (including UCC) was $20 182 per FTE student in government schools (excluding UCC this was $17 169). Between 2010‑11 and 2019‑20, real government expenditure (including UCC) per FTE student increased at an average rate of 1.7 per cent per year.

In-school expenditure per FTE student was higher for government secondary schools ($21 571 per FTE student) compared to government primary schools ($17 759 per FTE student). Out-of-school government expenditure per FTE student was substantially lower ($944 per FTE student) (table 4A.15).

Differences in the ‘student-to-staff ratio’ can provide some context to differences in the government recurrent expenditure per FTE student. Further information is available under Size and scope under the 'Context' tab.

6a. Efficiency

An objective of the Steering Committee is to publish comparable estimates of costs. Ideally, such comparison should include the full range of costs to government. This section does not report on non‑government sources of funding, and so does not compare the efficiency of government and non‑government schools.

School expenditure data reported in this section

Efficiency indicators in this section are based on financial year recurrent expenditure on government and non‑government schools by the Australian Government and State and Territory governments. Capital expenditure is generally excluded, but as Quality Schools funding and Students First funding cannot be separated into capital and recurrent expenditure, these payments are treated as recurrent expenditure in this section. Expenditure relating to funding sources other than government (such as parent contributions and fees) are excluded.

Sources of data — government recurrent expenditure on government schools

Total recurrent expenditure on government schools is unpublished data sourced from the National Schools Statistics Collection (NSSC) finance.

- Each State and Territory government reports its expenditure on government schools to the Government Schools Finance Statistics Group Secretariat. Recurrent expenditure on government schools comprises: employee costs (including salaries, superannuation, workers compensation, payroll tax, termination and long service leave, sick leave, fringe benefits tax); capital related costs (depreciation and user cost of capital [UCC]); umbrella departmental costs; and other costs (including rent and utilities). The Government Schools Finance Statistics Group Secretariat provides unpublished data on the UCC for government schools, imputed as 8 per cent of the written down value of assets (table 4A.13).

- The Australian Government reports its allocation to each State and Territory for government schools, consistent with Treasury Final Budget Outcomes — including the Quality Schools funding (from 1 January 2018), Students First funding (to 31 December 2017) and a range of National Partnership payments (table 4A.12).

- To avoid double counting, Australian Government allocations are subtracted from the State and Territory expenditure to identify ‘net’ State and Territory government expenditure (table 4A.10).

Sources of data — government recurrent expenditure on non‑government schools

Total recurrent expenditure on non‑government schools is sourced from unpublished data from State and Territory governments, and published data from the Australian Government as follows:

- Each State and Territory government provides unpublished data on its contributions to non‑government schools (table 4A.10).

- The Australian Government reports its allocation to each State and Territory for non‑government schools, consistent with Treasury Final Budget Outcomes — including the Quality Schools funding (from 1 January 2018), Students First funding (to 31 December 2017) and National Partnership payments (see table 4A.12).

Allocation of funding

Quality Schools Package — Australian Government

From 1 January 2018 the Australian Government introduced the Quality Schools Package replacing the Students First funding model which had been in effect since 1 January 2014. The Quality Schools Package is needs based. Commonwealth funding will be based on the Schooling Resource Standard that provides a base amount per student and additional funding for disadvantage. Students with greater needs will attract higher levels of funding from the Commonwealth. Funding is provided for government and non-government schools.

State and Territory governments

In general, State and Territory government schools systems are funded based on a variety of formulas to determine a school’s recurrent or base allocation, with weightings and multipliers added for students facing disadvantage. For non‑government schools, State and Territory governments also provide funding for recurrent and targeted purposes, usually through per capita allocations. Indexation of costs is normally applied to these funding arrangements for both the government and non‑government school sectors. Changes in overall funding by State and Territory governments across years is affected by all these factors, including enrolment numbers and school size, location and staffing profiles. Commencing 1 January 2019 with the signing of the National School Reform Agreement state and territory funding requirements are set as a percentage of the Schooling Resourcing Standard.

User cost of capital (UCC)

The UCC is defined as the notional costs to governments of the funds tied up in capital (for example, land and buildings owned by government schools) used to provide services. The notional UCC makes explicit the opportunity cost of using government funds to own assets for the provision of services rather than investing elsewhere or retiring debt.

UCC is only reported for government schools (not non‑government schools). It is estimated at 8 per cent of the value of non‑current physical assets, which are re‑valued over time.

Source: Australian Government Department of Education Skills and Employment (2020) https://www.education.gov.au/quality-schools-package-factsheet, accessed 9 October 2020.

7. Student outcomes (national testing)

‘Student outcomes (national testing)’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that Australian schooling aims for all young Australians to become successful lifelong learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed members of the community.

‘Student outcomes (national testing)’ is defined by two measures drawn from the National Assessment Program — Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) and National Assessment Program (NAP) sample assessments:

- National Assessment Program — Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN): NAPLAN testing is undertaken by students in years 3, 5, 7 and 9. Measures are reported for the proportion of students at or above the national minimum standard in NAPLAN testing and mean scale score for reading, numeracy and writing.

- Achieving (but not exceeding) the national minimum standard represents achievement of the basic elements of literacy or numeracy for the year level (ACARA 2021). The mean scale score refers to a mean (average) score on a common national scale.

- States and territories have different school starting ages resulting in differing average ages of students and average time students had spent in schooling at the time of testing. See table 4.2 for more information on average ages of students and average years of schooling across jurisdictions at the time of testing in 2021.

- From 2018, NAPLAN has been transitioning from pen and paper tests to online testing. For the 2018 transition year, the online test results were equated with the pen and paper tests. Results for both the tests are reported on the same NAPLAN assessment scale and so should be comparable with previous years.

- NAP Sample assessments: NAP national sample assessments are undertaken by students in year 6 and 10, on a triennial, rotating basis. Measures are reported for the proportion of students at or above the proficient standard in NAP assessments and mean scale score for Civics and citizenship literacy, Science literacy (testing undertaken by year 6 students only for all jurisdictions) and Information and communication technologies (ICT) literacy.

- The proficient standards, which vary across the tests, are challenging but reasonable levels of performance, with students needing to demonstrate more than minimal or elementary skills expected at that year level to be regarded as reaching them.

All data are accompanied by confidence intervals. See the 'Key terms and references' tab for details on NAPLAN and NAP confidence intervals.

A high or increasing mean scale score or proportion of students achieving at or above the national minimum standard (NAPLAN) or proficiency standard (NAP) is desirable.

Nationally for NAPLAN, the proportion achieving the national minimum standard in 2021 was statistically significantly:

- above that in 2008 for reading for Year 3 and Year 5 students and below for year 9, but there was no significant difference for Year 7 students (figure 4.7)

- above that in 2011 for writing for Year 3, but no significant difference for years 5, 7 or 9 students (table 4A.34)

- above that in 2008 for numeracy for Year 5 and below for Year 7 students, but there was no significant difference for Years 3 or 9 students (table 4A.38).

Mean scale scores are reported for reading, writing and numeracy in tables 4A.31, 4A.35 and 4A.39 respectively.

Students are counted as participating if they were assessed or deemed exempt (other students identified as absent or withdrawn are counted as not participating). In 2021, NAPLAN participation rates were at or above 90 per cent for most jurisdictions across testing domains and year levels (ACARA 2021).

Nationally for NAP in 2019, 53.0 (± 2.0) per cent of Year 6 students (table 4.1) and 38.0 (± 2.6) per cent of Year 10 students achieved at or above the proficient standard in Civics and citizenship literacy performance (table 4A.45). Mean scale scores for Citizenship literacy performance are in table 4A.46. National data on the proportion of students achieving at or above the proficient standard by special needs group (sex, Indigenous status, geolocation and parental occupation) are in table 4A.47.

Nationally in 2018, 58.0 (± 2.4) per cent of Year 6 students achieved at or above the proficient standard NAP in science literacy. Mean scale scores for NAP science literacy performance are in table 4A.43. National data on the proportion of students achieving at or above the proficient standard by special needs group (sex, Indigenous status, geolocation and parental occupation) are in table 4A.44.

Nationally in 2017, of Year 6 students and Year 10 students, 53 (±2.4) per cent and 54 (±3.0) per cent, respectively, achieved at or above the proficient standards in ICT literacy performance (table 4A.48). Mean scale scores for NAP ICT literacy are in table 4A.49. National data on the proportion of students achieving at or above the proficient standard by special needs group (sex, Indigenous status, geolocation and parental occupation) are in table 4A.50.

State/Territory | Average age and Years of schooling | Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 | Year 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NSW | Average age | 8 y 8 m | 10 y 7 m | 12 y 7 m | 14 y 7 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

Vic | Average age | 8 y 9 m | 10 y 9 m | 12 y 9 m | 14 y 9 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

Qld | Average age | 8 y 6 m | 10 y 5 m | 12 y 5 m | 14 y 5 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

WA | Average age | 8 y 5 m | 10 y 5 m | 12 y 5 m | 14 y 5 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

SA | Average age | 8 y 7 m | 10 y 7 m | 12 y 7 m | 14 y 7 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

Tas | Average age | 8 y 11 m | 10 y 10 m | 12 y 10 m | 14 y 10 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

ACT | Average age | 8 y 8 m | 10 y 7 m | 12 y 7 m | 14 y 8 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

NT | Average age | 8 y 6 m | 10 y 6 m | 12 y 6 m | 14 y 6 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m | |

Aust | Average age | 8 y 7 m | 10 y 7 m | 12 y 7 m | 14 y 7 m |

Years of schooling | 3 y 4 m | 5 y 4 m | 7 y 4 m | 9 y 4 m |

Source: ACARA (2021) National Assessment Program — Literacy and Numeracy Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2021 , ACARA, Sydney.

8. Attainment

‘Attainment’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that Australian schooling aims for all young Australians to become successful lifelong learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed members of the community.

‘Attainment’ (attainment rate) is defined as the number of students who meet the requirements of a year 12 certificate or equivalent expressed as a percentage of the estimated potential year 12 population. The estimated potential year 12 population is an estimate of a single year age group that could have attended year 12 that year, calculated as the estimated resident population aged 15–19 divided by five.

This indicator should be interpreted with caution as:

- assessment, reporting and criteria for obtaining a year 12 or equivalent certificate varies across jurisdictions

- students completing their secondary education in technical and further education institutes are included in reporting for some jurisdictions and not in others

- the aggregation of all postcode locations into three socioeconomic status categories (as a disaggregation for socioeconomic status) — high, medium and low — means there may be significant variation within the categories. The low category, for example, will include locations ranging from those of extreme disadvantage to those of moderate disadvantage.

A high or increasing completion rate is desirable.

Nationally in 2020, the year 12 certificate attainment rate for all students was 76 per cent. The rates increased as socioeconomic status increased. Across remoteness areas, the rates were substantially lower in very remote areas compared to other areas (figure 4.8).

The Child care, education and training sector overview includes data on the proportions of the population aged 20–24 and 20–64 years that attained at least a year 12 or equivalent or AQF Certificate II or above (that is school and non-school education and training to year 12 or equivalent or above) (tables BA.9–10).

9. Student outcomes (international testing)

‘Student outcomes (international testing)’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that Australian schooling aims for students to excel by international standards.

‘Student outcomes (international testing)’ is defined by Australia’s participation in three international tests:

- Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) — conducted by the IEA as a quadrennial international assessment — measures the proportion of sampled year 4 and year 8 students achieving at or above the IEA intermediate international benchmark, the national proficient standard in Australia for mathematics and science in the TIMSS assessment.

- Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) — conducted by the OECD as a triennial international assessment — measures the proportion of sampled 15 year old students achieving at or above the national proficient standard (set to level 3) on the OECD PISA combined scales for reading, mathematical and scientific literacy.

- Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) — conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) as a quinquennial international assessment — measures the proportion of sampled year 4 students achieving at or above the IEA intermediate international benchmark, the national proficient standard in Australia for reading literacy in the PIRLS assessment.

A high or increasing proportion of students achieving at or above the national proficient standard, or a high or increasing mean scale score is desirable.

TIMSS

Nationally in 2019, the proportion of students that achieved at or above the national proficient standard for the TIMSS:

- mathematics assessment was 69.6 (±2.5) per cent for year 4 students and 68.0 (±2.9) per cent for year 8 students (table 4.2)

- science assessment was 78.3 (±2.3) per cent for year 4 students and 74.2 (±2.4) per cent for year 8 students (table 4A.55).

Nationally in 2019, a higher or similar proportion of students achieved at or above the intermediate international benchmark compared to previous assessments. Results varied across jurisdictions (tables 4A.54–55).

PISA

Nationally in 2018, the proportion of Australian 15 year old students who achieved the national proficient standard in:

- reading literacy was 59.3 (± 1.3) per cent (table 4A.51)

- mathematical literacy was 54.2 (± 1.6) per cent (table 4A.52)

- scientific literacy was 58.1 (± 1.5) per cent (table 4A.53).

Across the three literacy domains, the proportions of Australian 15 year old students who achieved at or above the national proficient standard in 2018 were significantly lower than the proportions achieved in 2015 for science, but similar to results in 2015 for mathematics and reading (tables 4A.51-53). Compared to the OECD average in 2018, Australian 15 year old students scored:

- higher for reading literacy and scientific literacy

- the same for mathematical literacy (ACER 2019).

Data by Indigenous status, remoteness, socioeconomic background and sex for each literacy domain are reported in tables 4A.51-53.

PIRLS

Nationally in 2016, the proportion of year 4 students that achieved at or above the national proficient standard for reading literacy was 80.9 (± 2.1) per cent, a significant increase from 2011 although results vary by jurisdiction (table 4A.56).

Of the countries that participated in the PIRLS assessment, Australian year 4 students:

- significantly outperformed students from 24 other countries.

- were significantly outperformed by students from 13 other countries (ACER 2017).

10. Destination

‘Destination’ is an indicator of governments’ objective that Australian schooling aims for all young Australians to become active and informed members of the community positioning them to transition to further study and/or work and successful lives.

‘Destination’ is defined as the proportion of school leavers aged 15–24 years who left school in the previous year, who are participating in further education, training and/or employment. Data are reported for school leavers whose highest level of school completed was year 12, or year 11 and below.

A higher or increasing proportion of school leavers participating in further education, training and/or employment is desirable.

Data are sourced from the Survey of Education and Work and for this indicator relate to the jurisdiction in which the young person was resident the year of the survey and not necessarily the jurisdiction in which they attended school.

This Report includes information on the student destination surveys conducted by each State and Territory government, as context to this indicator (table 4.3). These surveys collect information from a larger number of students within relevant jurisdictions, but the research methods and data collection instruments differ which do not enable comparative reporting.

The proportion of all school leavers aged 15–24 years who left school in 2020 and who in 2021 were fully engaged in work or study was 74.6 per cent. This proportion compares to 63.2 per cent in the previous year (reflecting the impact of COVID-19), which was a decrease on earlier years (which ranged between 68.0 and 70.9 per cent) (figure 4.9). Proportions were higher for year 12 completers (77.7 per cent), compared to those who completed year 11 or below (60.2 per cent) (table 4A.59).

The Child care, education and training sector overview includes additional data on the participation of school leavers aged 17–24 years in work and study, including data on the Indigenous status of school leavers (tables BA.2–4).

Table 4.3 School leaver destination survey results

Key Features: | The NSW Post School Destinations and Experiences Survey commenced in 2010 and has been conducted annually since 2013, collecting information about students’ main destinations in the year after leaving school, either having completed Year 12 or left early. The survey includes students from government, Catholic and independent schools and can be completed online or via the telephone. In 2021 the survey was conducted between late August and mid-December. |

|---|---|

Statistics: | Data from the 2021 NSW Post-School Destinations Survey is currently unavailable due to a significant expansion in the sample size of the 2021 Destinations Survey. Findings from 2021 will provided in the 2023 Report on Government Services. |

Key Features: | In Victoria, a survey of post-school destinations (On Track) has been conducted annually since 2003. Consenting Year 12 or equivalent completers and Year 12 non-completers (from Years 10, 11 and 12) from all Victorian schools participate in a telephone or online survey early in the year after they leave school. |

|---|---|

Statistics: | The 2020 On Track Surveyed 26 735 (47 per cent participation rate) of the eligible 2019 Year 12 or equivalent completers cohort and 2012 students who had left school in Years 10, 11 or 12 (13 per cent participation rate of the Year 12 non-completer cohort), from government and non-government schools, as well as TAFE and Adult Community Education providers. Of the 26 735 Year 12 Completers, 75 per cent were in further education and training (54 per cent were enrolled at university, 12 per cent were enrolled at TAFE and 8 per cent had taken up apprenticeships or training). Of the 25 per cent not in education and training, 18 per cent were in full or part time employment, 6 per cent were looking for work and 1 per cent were not in the labour force, education or training, and 10 per cent deferred tertiary study. Of the 2012 Year 12 non-completers, 52 per cent were in education and training (2 per cent enrolled at university, 19 per cent were enrolled at TAFE and 30 per cent undertaking apprenticeships and training). Of the 48 per cent not in education and training, 22 per cent were in full or part time employment, 19 per cent were looking for work and 7 per cent were not in the labour force, education or training. |

Link: | On Track survey information and data can be accessed from the Victorian Department of Education website |

Key Features: | Since 2005, Queensland’s annual Next Step survey has captured information about the journey from school to further study and employment. The survey takes place approximately six months after the end of the school year and asks a range of questions regarding graduates' study and work choices. All students who completed Year 12 at government and non-government schools in Queensland are invited to participate and can complete the survey online or via the telephone. The 2021 survey ran from April to June and collected responses from 36 741 Year 12 completers, a 74.8 per cent response rate. |

|---|---|

Statistics: | In 2021, 90.0 per cent of respondents were engaged in education, training or employment six months after completing Year 12. A further 7.4 per cent were seeking work, while 2.6 per cent were not in the labour force, education or training. |

Link: | Survey outputs include individual school reports, sector and region reports, a statewide infographic and a report builder tool that allows users to create a custom report for their region of interest. Reports are available from the Next Step website (www.qld.gov.au/nextstep) on September 30 each year. |

Key Features: | A post school destination survey of WA government school Year 12 students from the previous year is conducted in March and April each year. The survey data are combined with university and TAFE data to build a comprehensive understanding of Year 12 students’ destinations. In March and April 2021, post-school destination information was collected for 9117 students (63.0 per cent of the total WA government school Year 12 student population in Semester 2, 2020). |

|---|---|

Statistics: | Of these students, 65.8 per cent were in either education or training, with 36.9 per cent at university, 5.5 per cent studying an apprenticeship or a traineeship, 11.6 per cent studying another type of nationally accredited training qualification, 2.1 per cent repeating Year 12 studies or engaged in non-accredited training and 9.8 per cent who had deferred their education or training. In addition, 5.8 per cent were engaged exclusively in full time employment, 14.4 per cent in part time employment, and 13.9 per cent were neither working nor studying. |

SA does not currently conduct a post-school destination survey. |

Tasmania does not currently conduct a systemic post-school destination survey. Recognising that continuing education equates to improved employment and life outcomes for students, the Education Act 2016 requires that:

To support the leaving requirements included in the Education Act 2016 the Department’s Youth Participation Database is a system that captures enrolment information about Tasmanians in Years 10 to 12 or equivalent. It brings together enrolment data from education and training providers across the state in order to identify young people without a current enrolment or exemption who require support to re-engage in a suitable education or training program. |

Key Features: | Since 2007, the ACT has conducted a telephone-based survey of all government and non-government students who successfully completed an ACT Senior Secondary Certificate in the preceding year, as well as students who left school before completing Year 12. The survey seeks information on the destinations of young people six months after completion of Year 12 and on satisfaction with their experience in Years 11 and 12. In 2018 this survey became multimodal with online self-completion and telephone interviews being utilised. In 2021, responses were received from 53 per cent of the 2020 Year 12 graduates who were sent a Primary Approach Letter. |

|---|---|

Statistics: | The 2021 survey (conducted between 21 May and 29 June) found that 94 per cent of 2020 Year 12 graduates were employed and/or studying in 2021 and overall 79 per cent found Years 11 and 12 worthwhile. Of the 67 per cent of 2020 graduates studying in 2021, 69 per cent reported that they were studying at the higher education (Advanced Diploma or higher) level and 28 per cent at the Vocational Education and Training (Certificate I-IV and Diploma) level. Of the 33 per cent of graduates who were not studying in 2021, 63 per cent intended to start some study in the next two years. Year 12 graduates who speak a language other than English at home were more likely to be studying (76 per cent) than those who did not (65 per cent). |

Link: | Published survey reports can be found at the ACT Education Directorate website. https://www.education.act.gov.au/ The 2020 report (latest published report) can be found at: |

The NT does not currently conduct a post-school destination survey. |

Source: State and Territory governments (unpublished).

Performance indicator data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in this section are available in the data tables listed below. Further supporting information can be found in the 'Indicator results' tab and data tables.

| Table number | Table title |

|---|---|

| Table 4A.18 | Student attendance rates, government schools, by Indigenous status (per cent) |

| Table 4A.19 | Student attendance rates, non-government schools, by Indigenous status (per cent) |

| Table 4A.20 | Student attendance rates, all schools, by Indigenous status (per cent) |

| Table 4A.21 | Student attendance rates, by Indigenous status and remoteness (per cent) |

| Table 4A.22 | Student attendance level, government schools, by Indigenous status (per cent) |

| Table 4A.23 | Student attendance level, non-government schools, by Indigenous status (per cent) |

| Table 4A.24 | Student attendance level, by Indigenous status and remoteness (per cent) |

| Table 4A.26 | PISA Sense of Belong at School Index, by selected equity group |

| Table 4A.27 | Apparent retention rates of full time secondary students, all schools (per cent) |

| Table 4A.28 | Apparent retention rates of full time secondary students, government schools (per cent) |

| Table 4A.29 | Apparent retention rates of full time secondary students, non-government schools (per cent) |

| Table 4A.30 | NAPLAN reading: Proportion of students who achieved at or above the national minimum standard, by Indigenous status and geolocation (per cent) |

| Table 4A.31 | NAPLAN reading: Mean scores, by Indigenous status and geolocation (score points) |

| Table 4A.34 | NAPLAN writing: Proportion of students who achieved at or above the national minimum standard, by Indigenous status and geolocation (per cent) |

| Table 4A.35 | NAPLAN writing: Mean scores, by Indigenous status and geolocation (score points) |

| Table 4A.38 | NAPLAN numeracy: Proportion of students who achieved at or above the national minimum standard, by Indigenous status and geolocation (per cent) |

| Table 4A.39 | NAPLAN numeracy: Mean scores, by Indigenous status and geolocation (score points) |

| Table 4A.44 | National Assessment Program, proportion of Year 6 students at or above proficient standard in science achievement performance, by selected equity group, Australia |

| Table 4A.47 | National Assessment Program, proportion of students at or above proficient standard in civics and citizenship achievement performance, by selected equity group, Australia |

| Table 4A.50 | National Assessment Program, information and communication technologies: proportion of students attaining the proficient standard, by selected equity group, Australia |

| Table 4A.51 | Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) reading literacy assessment |

| Table 4A.52 | Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) mathematical literacy assessment |

| Table 4A.53 | Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scientific literacy assessment |

Key terms

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students | Students are considered to be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin if they identify as being an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander or from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background. Administrative processes for determining Indigenous status vary across jurisdictions. |

Comparability | Data are considered comparable if (subject to caveats) they can be used to inform an assessment of comparative performance. Typically, data are considered comparable when they are collected in the same way and in accordance with the same definitions. For comparable indicators or measures, significant differences in reported results allow an assessment of differences in performance, rather than being the result of anomalies in the data. |

Completeness | Data are considered complete if all required data are available for all jurisdictions that provide the service. |

Confidence interval | A confidence interval is a specified interval, with the sample statistic at the centre, within which the corresponding population value can be said to lie with a given level of confidence (section 2). |

Confidence intervals (for NAPLAN and NAP sample) | The NAPLAN and NAP sample confidence intervals are calculated by ACARA and take into account two factors:

Estimates of sampling and measurement errors are combined to obtain final standard errors and confidence intervals to determine statistical significance of mean differences and percentage differences in NAPLAN and NAP sample performance within a report year. For analysing difference across years, a further source of error needs to be accounted for:

To evaluate statistical significance of mean and percentage differences between years, ACARA tests the change between years taking into account the equating, sampling and measurement errors. However, the equating error is not represented within the reported confidence interval. |

Foundation year | The first year of primary school. Naming conventions for the foundation year differ between states and territories. Foundation year is known as:

|

Full time equivalent student | The FTE of a full time student is 1.0. The method of converting part time student numbers into FTEs is based on the student’s workload compared with the workload usually undertaken by a full time student. |

Full time student | A person who satisfies the definition of a student and undertakes a workload equivalent to, or greater than, that usually undertaken by a student of that year level. The definition of full time student varies across jurisdictions. |

Geographic classification | From 2016, Student remoteness is based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure. The extended version of the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+), developed by the University of Adelaide’s Australian Population and Migration Research Centre, is the standard ABS‑endorsed measure of remoteness on ABS postal areas. Student remoteness (ARIA+) regions use the same ARIA+ ranges as the ABS remoteness areas and are therefore an approximation of the ABS remoteness areas. For more details of ARIA+ refer to <www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/ The remoteness categories are:

Geographic classifications prior to 2016 are based on the Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs (MCEECDYA) standard. Data are not directly comparable. (The exception is Census and survey data which were already using the ASGS, and prior to that the Australian Standard Geographic Classification). |

Geographic classification | Prior to 2016, Geographic categorisation is based on the agreed MCEECDYA Geographic Location Classification which, at the highest level, divides Australia into three zones (the metropolitan, provincial and remote zones).

|

In‑school expenditure | Costs relating directly to schools. Staff, for example, are categorised as being either in‑school or out‑of‑school. They are categorised as in‑school if they usually spend more than half of their time actively engaged in duties at one or more schools or ancillary education establishments. In‑school employee related expenses, for example, represent all salaries, wages awards, allowances and related on costs paid to in‑school staff. |

Low socio-educational background | Students in the lowest quartile of the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA). The ICSEA is a student level score constructed by ACARA from information (obtained from school enrolment records) relating to parents’: occupation; school education; and non‑school education. |

Out‑of‑school expenditure | Costs relating indirectly to schools. (See in‑school expenditure). |

Pre‑year 1 | See ‘foundation year’. |

Part time student | A student undertaking a workload that is less than that specified as being full time in the jurisdiction. |

Real expenditure | Nominal expenditure adjusted for changes in prices, using the General Government Final Consumption Expenditure chain price deflator and expressed in terms of final year prices. |

School | A school is an establishment which satisfies all of the following criteria.

|

Science literacy | Science literacy and scientific literacy: the application of broad conceptual understandings of science to make sense of the world, understand natural phenomena, and interpret media reports about scientific issues. It also includes asking investigable questions, conducting investigations, collecting and interpreting data and making decisions. |

Socioeconomic status | As identified in footnotes to specific tables. |

Socio‑educational background | See ‘Low socio‑educational background’. |

Source of income | In this chapter, income from either the Australian Government or State and Territory governments. Australian Government expenditure is derived from specific purpose payments (current and capital) for schools. This funding indicates the level of monies allocated, not necessarily the level of expenditure incurred in any given financial year. The data therefore provide only a broad indication of the level of Australian Government funding. |

Special school | A special school satisfies the definition of a school and requires one or more of the following characteristics to be exhibited by the student before enrolment is allowed:

|

Student‑to‑staff ratios | The number of FTE students per FTE teaching staff. Students at special schools are allocated to primary and secondary (see below). The FTE of staff includes those who are generally active in schools and ancillary education establishments. |

Student | A person who is formally (officially) enrolled or registered at a school, and is also active in a primary, secondary or special education program at that school. Students at special schools are allocated to primary and secondary on the basis of their actual grade (if assigned); whether or not they are receiving primary or secondary curriculum instruction; or, as a last resort, whether they are of primary or secondary school age. |

Students with disability | Students are counted in the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability where:

The DDA provides a broad definition of disability. The DDA covers individuals with disability, associates of a person with a disability, people who do not have a disability but who may face disability discrimination in the future, people who are not in fact impaired in functioning but treated as impaired, and people with conditions such as obesity, mild allergies or physical sensitivities, and those who wear glasses. |

Teaching staff | Teaching staff have teaching duties (that is, they are engaged to impart the school curriculum) and spend the majority of their time in contact with students. They support students, either by direct class contact or on an individual basis. Teaching staff include principals, deputy principals and senior teachers mainly involved in administrative duties, but not specialist support staff (who may spend the majority of their time in contact with students but are not engaged to impart the school curriculum). For the NT, Assistant Teachers in Homeland Learning Centres and community school are included as teaching staff. |

Ungraded student | A student in ungraded classes who cannot readily be allocated to a year of education. These students are included as either ungraded primary or ungraded secondary, according to the typical age level in each jurisdiction. |

VET in Schools | VET in Schools refers to nationally recognised VET qualifications or accredited courses undertaken by school students as part of the senior secondary certificate. The training that students receive reflects specific industry competency standards and is delivered by an external Registered Training Organisation (RTO), the school or school sector as an RTO and/or the school in partnership with an RTO. VET courses may require structured work placements and may be undertaken as a school‑based apprenticeship or traineeship. |

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2022, Schools Australia, 2021, Canberra.

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) 2021, National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2021, Sydney.

ACER (Australian Council for Educational Research) 2019, PISA 2018: Reporting Australia’s Results. Volume I Student Performance, ACER Australia.

—— 2018, PISA Australia in Focus: Number 1 – Sense of belonging at school, ACER, Australia.

—— 2017, PIRLS 2016: Reporting Australia’s results, ACER, Melbourne.

Boon, H.J. 2011, ‘Raising the bar: ethics education for quality teachers’, Australian Journal of Teacher Education, vol. 36, pp. 76–93.

Bruckauf, Z. and Chzhen, Y., 2016, Education for All? Measuring inequality of educational outcomes among 15‑year‑olds across 39 industrialized nations, Innocenti Working Papers no. 2016_08, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

COAG 2018, National School Reform Agreement, https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/national_school_reform_agreement_9_0.pdf (accessed 9 October 2020).

—— 2009, COAG Meeting Communique April 2009, https://www.coag.gov.au/meeting-outcomes/coag-meeting-communique-30-april-2009 (accessed 21 November 2019).

EC (Education Council) 2019, Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration, http://www.educationcouncil.edu.au/Alice-Springs--Mparntwe--Education-Declaration.aspx (accessed 9 October 2020).

Fredricks, J., Blumenfeld, P., Paris, A. 2004, ‘School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence’, Review of Educational Research, vol. 74 Spring 2004,

pp 59–109.

Hattie, J.A. 2009, Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta‑analyses Relating to Achievement, Routledge, New York, USA.

Hancock, K. J., Shepherd, C. C. J., Lawrence, D. and Zubrick, S. R. 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts. Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Canberra.

NCVER (National Centre for Vocational Education Research) 2021, VET in Schools 2020, Adelaide.

PC (Productivity Commission) 2012, Schools Workforce, Research Report, Canberra.

PM&C (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) 2014, Roles and responsibilities in education, Part A: Early Childhood and Schools, Reform of Federation White Issues Paper 4, Canberra.

UNESCO‑IBE. (United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organisation – International Bureau of Education) (2016), What Makes a Quality Curriculum?, UNESCO International, Bureau of Education, Geneva, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002439/243975e.pdf (accessed 23 October 2017).

Download supporting material

- 4 School education data tables (XLSX - 748 Kb)

- 4 School education dataset (CSV - 2587 Kb)

See the corresponding table number in the data tables for detailed definitions, caveats, footnotes and data source(s).